“We have never preached violence, except the violence of love, which left Christ nailed to a cross.” – Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero | November 27,1977

The date has been set. October 14, 2018 has been chosen by the Vatican as the day for the canonization of the slain Salvadoran archbishop, Oscar Arnulfo Romero.

The ceremony will take place in Rome, perhaps in the Sistine Chapel with the beautifully painted ceiling, but the real festivals will spring up all around our graffiti adorned world as the disadvantaged gather to celebrate the new saint of the poor.

When Romero was hand picked by the church and state to lead El Salvador’s faithful it was assumed he would merely maintain the status quo of this country where Roman Catholic rituals permeate every corner of society. Yet from the beginning he was a problem, even rejecting a life spent overlooking the city from a large estate in-favor of a small home below, mixed in with the people.

The Archbishop’s messages began to change over his three years, as more homilies started speaking of a new way. A way where change could happen sooner; an idea that the meek shouldn’t need to wait until death to inherit the earth.

It’s Liberation Theology, and the ideas from South American were not then, nor now, favored by the powerful.

It’s Liberation Theology, and the ideas from South American were not then, nor now, favored by the powerful.

So it was, on a Monday almost 40 years ago, that a dusty red Volkswagen stopped in front of a small church on the grounds of the cancer hospital. Worship had begun and the doors were swung wide, welcoming all.

Only moments before, Oscar Romero had walked the few short steps from his three room home to celebrate the Eucharist with his neighbors.

No one noticed the trained gunman stepping from the small car, then carefully aiming his riffle down the aisle. Suddenly a shot rang out and Romero staggered, then fell to the floor, his heart pumping blood over the scattered host.

A peacemaker was dead from an assassin’s bullet on that sunlit Monday morning of March 24, 1980.

There were no arrests, no trials, no punishment for the killer or the political leaders responsible for the 62 year old’s death. Romero had been the voice for those without voice and now his words were silenced. Or were they?

The elite may have muffled one man, but they could never silence his message of love. His words would live on in every voice that cries out for change. Including my own.

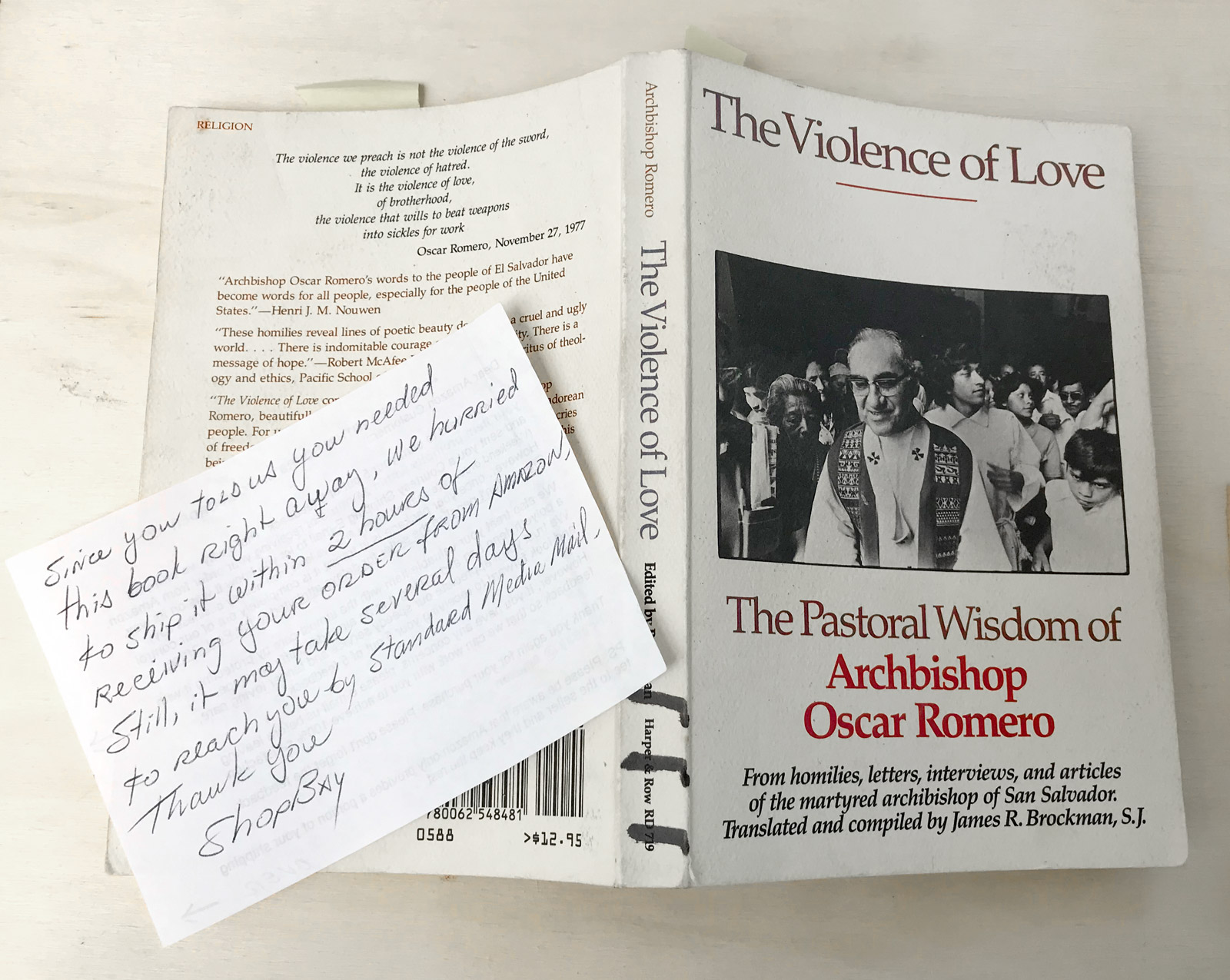

I first traveled to El Salvador in 2005 as part of a Habitat for Humanity brigade building homes. I was full of questions on that first visit when our leader offered me her book. The Violence of Love is a collection of homilies, letters, interviews and articles of the martyred archbishop.

I’m not Catholic so I doubted the book would help much, but as I read a few pages, followed by more, I asked if I could keep reading and even underline some spots. By the end of the trip it was so marked up that I promised to buy her a new copy as soon as we got home.

The picture at the top is from a visit in 2007. It shows a small section of a wall depicting the troubled history of El Salvador. The Metropolitan Cathedral of the Holy Savior is close by.

I’ve spent time at the wall, always in silence, trying to understand those horrible years. I’ve attended worship in the cathedral with all its pomp.

I’ve also been on the lower level with the people, near Oscar Romero’s tomb, where everything seems more relaxed. I’ve stood in line to use the restrooms, constructed in back as if as a crumb being tossed to the poor, to the street vendors and panhandlers while they earn money for their dangerous trip north.

I’ve also prayed in the small church on the grounds of the cancer hospital. I’ve walked through its open doors and stood at the altar in that dreadful spot.

I’ve looked back up the aisle, trying to imagine the feelings in the hearts of both men: one offering the hope of the elements and the other pointing his weapon of war to take that hope away.

I’ve spent time in each of his three rooms and peered into his car parked outside. That old black sedan was his way of moving around his country, blending into its beauty, without ever being the main event. I’ve visited with the women of the hospital preparing vegetables under the large shade tree, just as other women must have done 40 years ago.

Through it all, I hope I’ve gained some wisdom. Wisdom about choices – on which ones are right and which are wrong and what happens when the rules are not fair for everyone when we are playing the same game.

Some would like the ceremony to be held in San Salvador, near his tomb; but I think Rome is the better choice. Rome makes it clear that Blessed Romero is a saint for the world and not just El Salvador.

Why do you think some faith leaders are outspoken voices for the oppressed while others say so little about our current political and social justice issues?

When is it time for action and when Is laissez-faire best?

As always the conversation starts here.

“In the ordinary choices of every day we begin to change the direction of our lives.” – Eknath Easwaran

This prayer of Romero’s taught me who’s in charge of a future when it’s not my own.

It helps, now and then, to step back and take a long view.

The kingdom is not only beyond our efforts, it is even beyond our vision.

We accomplish in our lifetime only a tiny fraction

of the magnificent enterprise that is God’s work.

Nothing we do is complete, which is a way of saying

that the kingdom always lies beyond us.

No statement says all that could be said.

No prayer fully expresses our faith.

No confession brings perfection.

No pastoral visit brings wholeness.

No program accomplishes the church’s mission.

No set of goals and objectives includes everything.

This is what we are about.

We plant the seeds that one day will grow.

We water seeds already planted,

knowing that they hold future promise.

We lay foundations that will need further development.

We provide yeast that produces far beyond our capabilities.

We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of liberation

in realizing that. This enables us to do something,

and to do it very well. It may be incomplete,

but it is a beginning, a step along the way,

an opportunity for the Lord’s grace to enter and do the rest.

We may never see the end results, but that is the difference

between the master builder and the worker.

We are workers, not master builders; ministers, not messiahs. We are prophets of a future not our own.”

– Amen

Epilogue

If you’d like your own copy of The Violence of Love, it’s available from your local bookseller or Amazon.

But, if you don’t mind the underlining and notes, you can borrow mine. After all, it was passed on to me by a friend and I will gladly share it with you – if you promise a prompt return.

Oscar Romero is one of my heroes. Thank you for sharing your connection.

George –

I’m glad you read the story and that Romero is one of your heroes. He certainly is one of mine. His words impact my thinking daily.

– Bruce

Thank you, Bruce. Your memoir brings bacr so many memories of our trips to El Salvador: inspiring, fun, bittersweet.

Thanks, Jeff. Yes, those trips were special in so many ways. And thanks for reading and commenting.

– Bruce